I remember as a kid that even a person who wore eyeglasses was ridiculed (“four-eyes!”). People who stuttered were ignored, mimicked or teased. Manufactured prosthetics, for those with missing parts, were in a creative infancy born of war wounds. And people who really, really didn’t fit the norm were to be somewhat if not entirely hidden and/or shamed. Sometimes maybe they became a feature attraction and got employed by a circus.

Truly, with such cultural conditioning, I was well into my art training before I realized one didn’t need 20/20 vision to be a visual artist.

I’ve heard it said that if one sense is absent the rest are heightened. I have a dear friend who has had a major genetically-acquired hearing impairment since birth. I asked her if she thought her other senses were heightened and she responded with an emphatic YES. I found that reassuring at the time. I’m finding all physical differences impressive after discovering more about the creative cross-disability solidarity of the art world. I wonder what new sense worlds could open from the non-normative?

Decidedly non-normative, yet simply labeled neurodivergent and not disabled, are artists with autism currently being heralded for their work. British artist Stephen Wiltshire has a photographic memory. He was diagnosed autistic at age three, has been drawing since age five, and at age forty-eight is well established internationally. His detailed architectural drawings are pleasing to most audiences.

The art online resource, Hyperallergic, recently profiled Mike Hack’s exhibit (https://hyperallergic.com/tag/mike-hack/) at the Haul Gallery, Brooklyn. The show announcement described the artist simply as “a person with autism.” Hack’s video work, described as “slyly irreverent” emphasizes his agency as an artist and autistic.

ABLEISM. If unfamiliar with the term, it generally means “discrimination in favor of able-bodied people.” Here in Portland, Oregon in 2022, it’s obvious that being able to ride a bicycle is favored by city planners.

Google says: “Ableism is the discrimination of and social prejudice against people with disabilities based on the belief that typical abilities are superior. At its heart, ableism is rooted in the assumption that disabled people require 'fixing' and defines people by their disability.”

Ableism is cultural. It takes all forms, large and small, yet is always disruptive to some. Ableism is invisible to many and most closely observed, announced and denounced by people with disabilities. Smashing barrier curbs at corners with sledgehammers brought attention to the difficulty of navigating such platform changes for mobility-challenged users. Now ramped corners are typical in the U.S. They intended to ease the way for wheelchairs, walkers, and necessarily slow- or leisurely-moving pedestrians. Bicyclists, babies in strollers, people lugging suitcases or whatnot, and toddlers discovered benefit too. And so the practice is widely embraced and supported.

Another civic feature addressing movement is tactile paving—the bright yellow patches of raised bumps and/or linear lines helping low-vision and blind people navigate corners, stairs, train stations, and any complicated public area. It alerts people to a change. Tactile paving is still not totally embraced in the U.S., especially in countryside settings, but has a growing and solid urban presence. It originated in Japan, by Seiichi Miyake back in the 1960s. His impulse was to help a blind friend get around town. Fifty or so years later, it is widely embraced internationally. Watlington [see link; arts now] maintains that “impairment has long been at the heart of creativity.”

Watlington also states that many “deaf artists advocate changing the term ‘hearing loss’ into ‘deaf gain.’” Sensitivity to sound is a priority given strength by challenge. What with the use of ear buds and advanced technology, wearing hearing aids is no longer (as it was formerly) announcing a weakness. This has the disadvantage of people not recognizing impairment and speaking too softly (heard as “mumbling” to some). No system suits all and that is the necessary focus. Watlington points out the need for a flexible spirit.

Many American theaters have added hearing and vision aids. See AARP’s https://blog.aarp.org/healthy-living/love-theater-but-cant-hear-it-four-show-stopping-solutions for selected details.

As well-intentioned as some adjustments generated by the so-called able-bodied are, an important rallying cry from the people with disabilities is “nothing about us without us.” For example, Braille wall labels at art shows are not particularly helpful if they only tell Braille readers technical stuff—title, artist, date, dimensions. That does not allow blind people enough room to create an image in their head. Essentially the blind are left blind to the specific artwork.

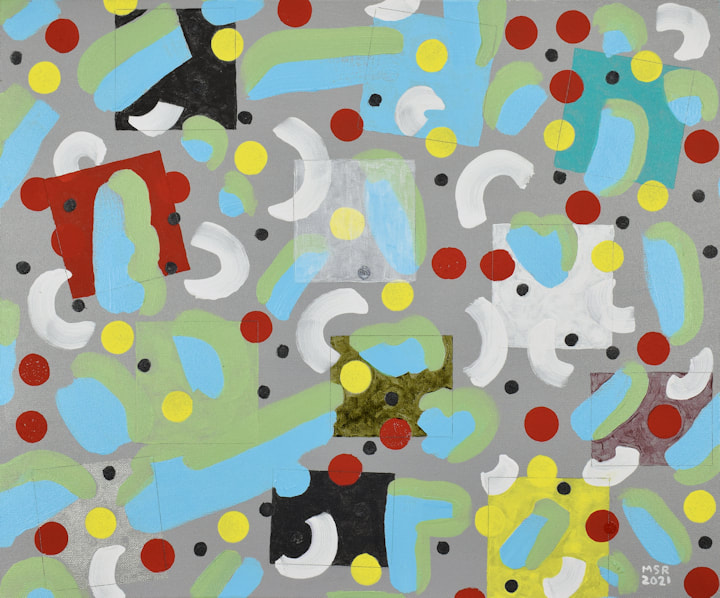

Last year I made an artwork Ways of Seeing, Ways of Non-Seeing (see below). It was inspired by the New Yorker book review on “There Plant Eyes: A Personal and Cultural History of Blindness” by M. Leona Godin [Vintage Publishing, 2021]. What attracted me is the point that Godin argues: “There are as many ways of being blind as there are of being sighted.”

Andrew Lelard’s article, “Ways of Not Seeing,” addresses blind visual artists’ presentations, nincluding dance, traditional art, filmmaking and performance. And do low-vision or blind visual artists need to consider the sighted as mainstream and work accordingly? What of reaching the deaf? Can blindness be a force, a superpower?

Museums frequently provide audio descriptions (AD) for challenged exhibit visitors. Apparently, AD has long and somewhat inept industry guidelines, ostensibly to produce “objective” content. They’re not objective of course. Such content never can be. Just the content and sequencing of information suggests a ranking.

Though captioning is an option for deaf audiences who can read, audio descriptions also can add texture, enjoyment or confusion to films offered to a wide audience. Yet as a filmmaker is AD to be incorporated into the movie’s focus, added later by an objective (emotionless) writer, or is it even wanted or needed?

Filmmaker Evans, a tactile, low-vision director making films for everybody, not just the blind, sought the advice of Georgina Kleege. “She basically said: stay involved, make it a part of your creative process.” That worked for him when he found a vocalist and writer who clicked creatively. Some viewers enjoy the extra attention to detail it can provide. And some blind people do appreciate well realized AD.

Artist Emilie L. Gossiaux, using visual art as expression while blind, is offended to be promoted as a “blind artist.” The roundtable in Leland’s article agreed. It is often an attempt to sensationalize what’s on offer. Gossiaux is not making blind art, she’s making art. She is not a blind artist. She’s an artist. Just as some of us have learned that a person who developed diabetes is not a diabetic. The person simply has diabetes. We are not our condition.

Art in America is featuring visual artist Gossiaux in an article written by Emily Watlington, “Drawing Beyond Sight.” A.I.A. will be discussing disability culture for the month of October, 2022. There’s a lot going on in the art community and beyond. And remember, as disability design advocate Liz Jackson said, “We [disabled people] are the original lifehackers” and going strong.

https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/interviews/blind-artists-roundtable-1234641927/#recipient_hashed=307fbcf3cd722a4f8d8efd1cab75119e7a60713fdd5512f73f8bd808749afab0&recipient_salt=b91dbb757b8f134b462f764546de428eb9574ef8fcb9fd40b72547cd783be0a9

https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/features/disability-arts-now-1234642326/#recipient_hashed=307fbcf3cd722a4f8d8efd1cab75119e7a60713fdd5512f73f8bd808749afab0&recipient_salt=b91dbb757b8f134b462f764546de428eb9574ef8fcb9fd40b72547cd783be0a9

https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/interviews/emilie-gossiaux-1234641886/#recipient_hashed=307fbcf3cd722a4f8d8efd1cab75119e7a60713fdd5512f73f8bd808749afab0&recipient_salt=b91dbb757b8f134b462f764546de428eb9574ef8fcb9fd40b72547cd783be0a9